How much responsibility do patients have for their own health?

Technological and demographic change is confronting the healthcare system with unprecedented challenges.

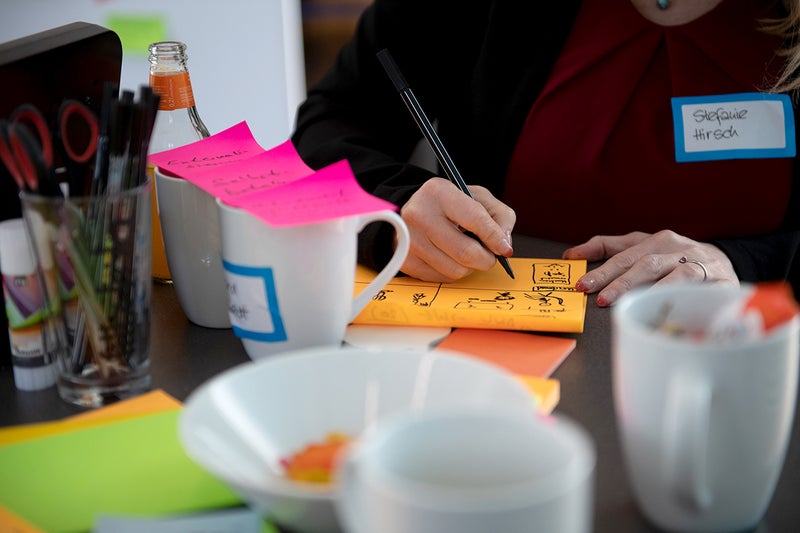

In order to find out to what extent people in the 21st century are responsible for their own health and what they need to be aware of, we invited experts from medicine, health insurance companies and the health care industry to participate in a workshop with patients: In the “Neue Denkerei” (New Think Tank) innovation laboratory in Kassel, these transdisciplinary experts worked on novel solutions for new challenges—without limiting their thinking or wearing blinders.

Dr. Stefan Bösner doesn’t have an answer. But only when he’s asked about his presentation. The general practitioner and university professor from Marburg has just presented a new idea about how to get patients to take better care of their health with the help of pictures, slides and Lego bricks. The 53-year-old developed the product together with a health insurance company representative, a stoma patient and an IT entrepreneur. Workshop leader Zwetana Penova wants to know what the product's name should be. Bösner shrugs. He seems to be asking: Does it really matter? Isn't it much more interesting whether the product would work in reality? “Healthpal”, suggests one of the group. Stefan Bösner smiles. Not bad.

Six hours earlier: Ten people from all over Germany meet for the first time in the "Neue Denkerei” co-creation space, a former print shop in the heart of Kassel. High walls, heavy steel beams, many movable walls with colorful graphics and workshop materials. Each participant has a very special area of expertise – Big Data, medical knowledge, user experience (UX), philosophy, management, and, above all, life experience. Because every person is a potential patient, who has an interest in ensuring that our health system continues to function for a long time to come.

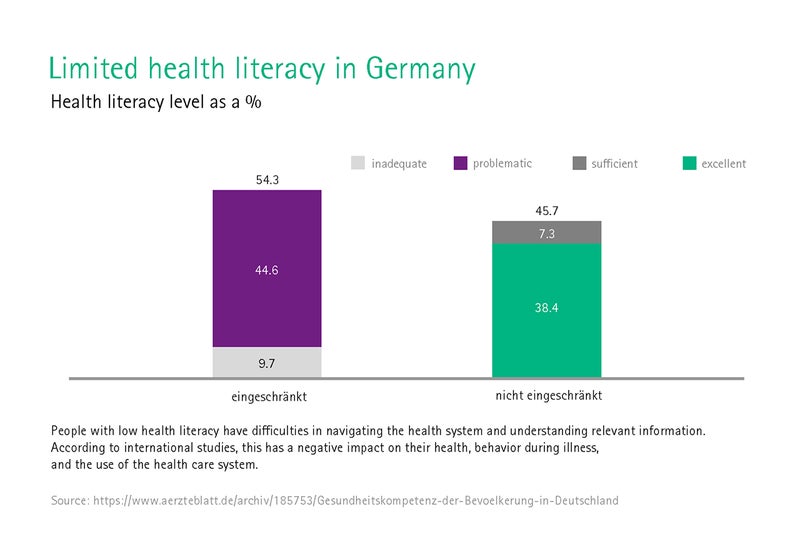

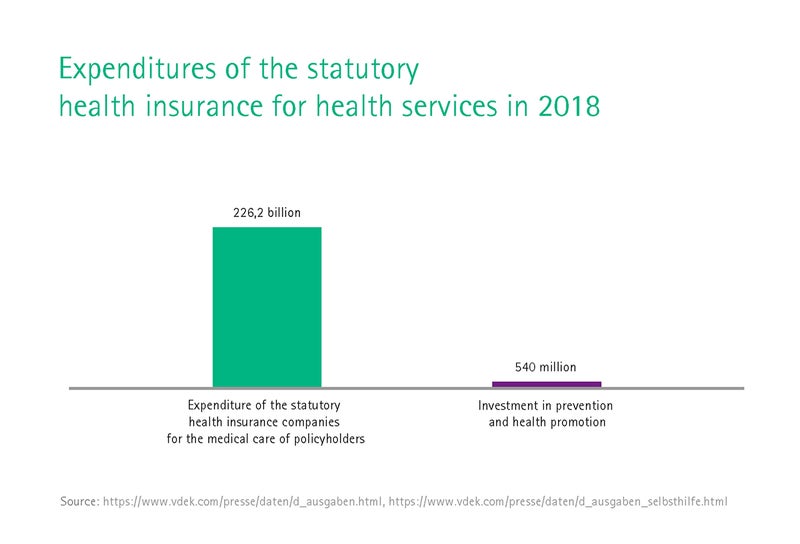

“We are facing a problem that we can only solve together,” says Dr. Meinrad Lugan, Member of the B. Braun Management Board. Health costs are rising every year. While treatments are becoming more and more technical and expensive, 56 percent of people today already have limited health competence and can hardly find their way around this hyper-complex system. “We don't want to hold any monologues today,” Lugan says, referring to the motto, “but to enter into dialog.” The research questions of the day are displayed on the screen:

(1) How can the system empower individuals to maintain their health?

(2) And how much responsibility does the individual actually bear?

The participants form two groups: The "Users" team and the "System" team. In the next few hours, the status quo is attacked from two sides, bottom up + top down.

10.45 AM: What Drives People?

In one corner of the room, B. Braun board member Meinrad Lugan, medical ethics professor Dominik Groß and UX specialist Claudia Sinnig sit on a kind of wooden platform listening to Timo Hertwig: Just a few years ago, the 39-year-old machine installer from northern Hesse weighed 150 kilograms, and he ended up in the hospital with high blood pressure and a ruptured intestine. "I knew I couldn't go on like this," says Hertwig. “First I went for walks, then I started running. Small goals that seemed achievable.” His workshop colleagues are emphatic and impressed: especially because it’s hard to believe this anecdote from the looks of this slim, athletic man with the bright eyes. “For physicians, there is nothing better than self-effective patients,” says Dominik Groß. The workshop group now wants to find ways to reproduce Timo’s success story as often as possible. The consensus: the world is ready for good ideas.

Claudia Sinnig: “Health, mindfulness, climate protection are currently totally hip – or is that just my Berlin bubble?

Dominik Groß: “In the past, Gaulloise cigarettes were an icon for intellectuals. Today, smokers are hardly seen at the university.”

Meinrad Lugan: “But what is health, exactly? Are we concerned with the medical definition or the subjective well-being of people?”

An initial learning effect: Before starting to solve the problem, a common understanding of the task must be developed. The other working group is dedicated to deconstruction: “My first approach would be to break the question down into parts,” says Julia Schröder, prevention expert at BKK.

Stefan Bösner, general practitioner: "An often hidden fact: Not all doctors want informed patients. Because if people are empowered, then someone else must also give up power."

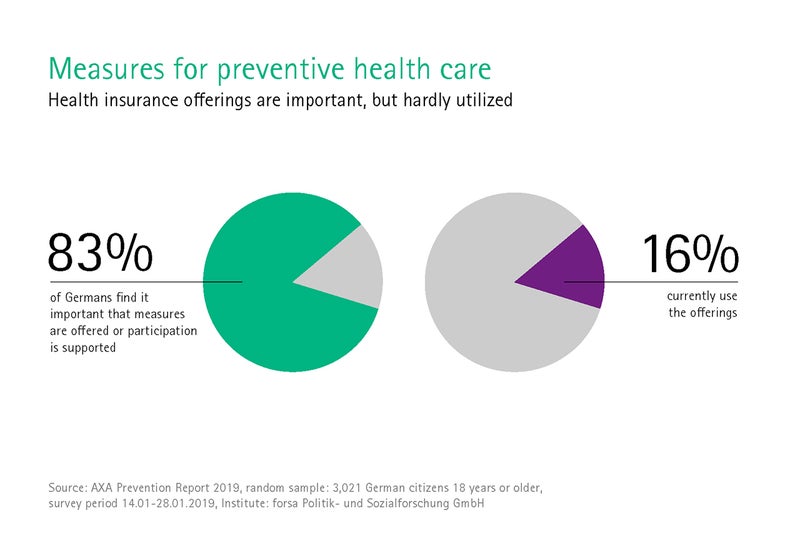

Julia Schröder: "Most preventative programs only reach people who are already well, and this increases the 'social gap'. The question is: Why don't people in precarious circumstances react to what’s offered to them?"

Stefan Bösner: “There are also reasons for this that lie outside the health care system. A single mother of three often has no time for prevention.”

Jan Hacker, entrepreneur: “What you get in return is so unclear. Does jogging lead to better blood pressure? Or to arthritis in your knees? How can one deal with the 'delayed gratification’ problem?

Ekkehard Mittelstaedt, Managing Director of MGS GmbH: "You have to admit it: Not wanting to know is a human right. But the consequences of this decision must be made clear to everyone."

Stefanie Hirsch, administrative employee at an insurance company, and stoma patient: "The information is scattered all over. An employee needs different information than a young person. I often wonder when reading a brochure: Do they even mean me?"

11:30 AM: The Core of the Problem

The workshop group meets in plenary, a kind of mini-parliament between the working sessions, where ideas are presented and the next steps are discussed. After the basic problems have been identified, tasks are derived from them: "How can we support ______ to achieve _______? The workshop participants now throw ideas on the wall. Soon, a colorful tile mosaic appears on the movable walls. Zwetana Penova says: “This step is about quantity and not quality. Just write down whatever pops into your head.”

The "Users" team has set itself the goal of creating a product to help a 15-25 year old digital native with the tendency to be overweight. The Post-it notes just fly up on the wall:

• Nutrition as a subject in school

• Training for parents

• Instagram posts from affected people

• Start augmented reality contests among friends

• Free fitness studio

• CO2 certificates for jogging

• …

After ten minutes, the four experts stand in front of the colorful wall and try to cluster the ideas into categories such as education, incentives, and compulsion. Everyone rejects the last approach. And not just because a piece of paper says “neuro-implant” (behind which the author has scribbled: “not possible”). There are no prohibitions on thinking in this workshop.

In the second group, one still struggles with the scope of the task. "We are a team of philosophers," says Ekkehard Mittelstaedt, Managing Director of MGS E-Portal GmbH and long-standing Managing Director of the German Federal Association of Health Care IT. They don’t start with patients or people, they ask themselves what tools the health care sector players need to support patients better.

Ekkehard Mittelstaedt: “We definitely need a dynamic competition of methods in the health sector instead of always waiting for a big solution that never comes”.

Julia Schröder: “Health education in schools could provide systematic and professional knowledge: exercise, nutrition, digitalization.”

Jan Hacker: “With their high burn-out rate, are teachers really the best communicators of health information?”

Stefan Bösner: “There is so much information and so many tutorials. Instead of new projects, as a doctor I sometimes wish for a kind of meta-search engine that filters all this and makes it accessible.”

1:00 PM: An Idea Takes Shape

The workshop team meets again in plenary. Now they have a lot of ideas. But how can they make them tangible, and test them? “The future is too complex to be thought through carefully,” says Zwetana Penova. "That's why it helps to first record a scenario or visualize future images." As a first step, the groups now evaluate the existing approaches using adjectives such as "empathic", "innovative" and "realistic" - then each team selects an idea to develop into a prototype. Penova gives them another piece of advice: "Don't ask, 'what's wrong with the idea? Ask instead: ‘what could it look like?’”

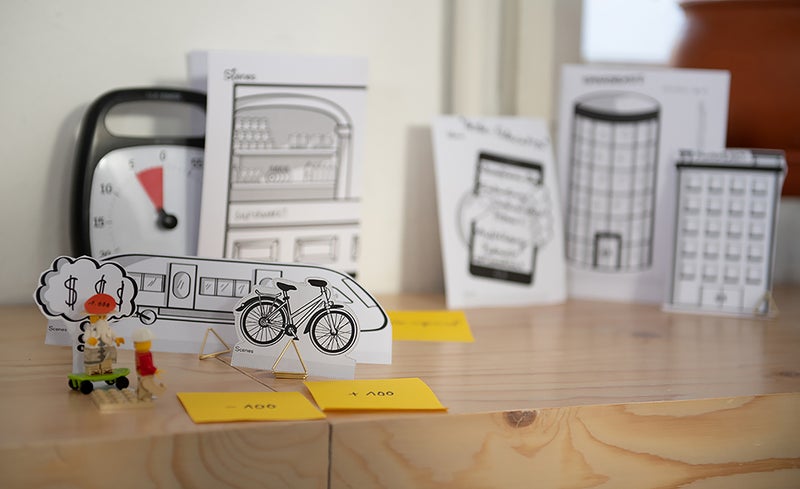

On a table are Lego Play bricks and figures and ‘scenes”, pictures developed to foster innovation at the software company SAP. Images of smartphones, people, houses, cities. None of the participants think it’s strange to play with toys or children’s arts and crafts. There is lots of laughter. Finally: doing instead of discussing.

The “User” team is working on an augmented reality app that calculates a fitness score for a user. The UX designer, Claudia Sinnig, uses a small Lego figure, who parks the car at the side of the road and rides into town by bike. The system - symbolized by a smartphone icon - recognizes this automatically and rewards the decision: a new score appears on a small paper thought bubble: +100 points.

Meinrad Lugan: “To get people to play along, affected influencers could tell their story on Instagram.”

Timo Hertwig: “It is important to be able to measure yourself against others.”

Claudia Sinnig: "The score can’t be too ‘virtual’. Money is still the best incentive. Can we tie the score to taxes or the insurance companies?"

Dominik Groß: "Participation in this kind of system must be voluntary, of course. We don't want patient data exposed. And no unencrypted data must be allowed to reach the health insurance companies.”

3:00 PM: Raising the Curtain on the Future

After the team “User” has presented its idea to the plenum, the prototype of team “System” follows. Team “System” also visualizes the prototype in a complex setting: And they use very similar icons and symbols – dollar signs, smartphones, and sports equipment. Team “User” and Team “System” seem to approach a related solution from two directions. The “System” team begins with a role play. Stefanie Hirsch, a stoma patient for two years, meets the general practitioner Stefan Bösner. The mood is relaxed. They’ve gotten to know each other well in the past few hours.

Stefan Bösner: “Hello, you look good. What can I do for you?”

Stefanie Hirsch: “After the last operation I still feel weak.”

Stefan Bösner: “You have also lost a lot of weight. What do you say we set ourselves the nice goal of putting on five kilos in the next three months? I can write you a prescription and set up a program for you.”

Stefanie Hirsch: “Yeah, sounds good!”

The scene ends. The economist Ekkehard Mittelstaedt steps forward. “A contract was made,” he says, almost solemnly. The product, which the group will later christen "Healthpal", rewards the participant’s behavior, just like a Paypal account. Mittelstaedt explains the principle: "Let’s assume that the therapy costs 100 euros. Patients always pay 10 percent. However, if she achieves the goals agreed upon with the doctor through discipline and therapy-appropriate behavior, then she will receive Healthpal points which can be redeemed with her health insurance company. Mrs. Hirsch sees the therapy’s success, not just on her scale, but also in her wallet."

The group thinks this is an exciting idea. Because it is an individual goal, which incorporates different life situations and definitions of health and treatment success. Because it provides incentives to behave in accordance with therapy. And because it places doctors between patients and health insurance companies, as trusted persons who can independently monitor compliance with the goals. On the other hand, the health insurance companies might benefit, because expensive follow-up costs are reduced and the data provides an overview of promising therapies. The Healthpal prototype is undoubtedly new and innovative – but is it feasible?

Prof. Dr. Dr. Dr. Dominik Groß, Director of the Institute for History, Theory and Ethics of Medicine at the University of Aachen:

"It's a paradox: All too often, during discussions we think only in solutions. But this tunnel vision means that we lack the creativity needed to find truly innovative solutions to problems.”

Dr. Meinrad Lugan, Member of the Management Board of B. Braun Melsungen AG, Board Member MedTech Europe:

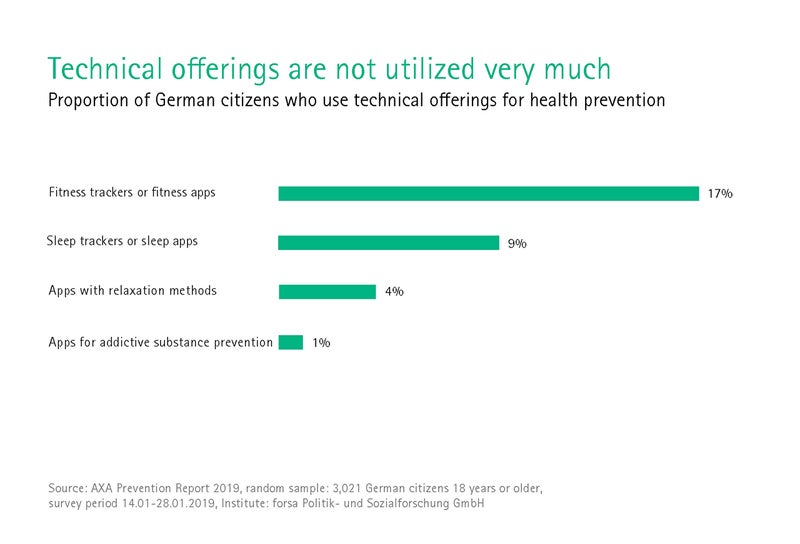

“We know what's good for your health. Millions of people wear fitness bracelets, use health apps, and get "knowledge" from Dr. Google. We have more data than ever before. But are we drawing the right conclusions from it? Why don't we use this enormous knowledge? We have to find new ways to do this."

Prof. Dr. Dr. Dr. Dominik Groß, Director of the Institute for History, Theory and Ethics of Medicine at the University of Aachen:

"It's a paradox: All too often, during discussions we think only in solutions. But this tunnel vision means that we lack the creativity needed to find truly innovative solutions to problems.”

Dr. Meinrad Lugan, Member of the Management Board of B. Braun Melsungen AG, Board Member MedTech Europe:

“We know what's good for your health. Millions of people wear fitness bracelets, use health apps, and get "knowledge" from Dr. Google. We have more data than ever before. But are we drawing the right conclusions from it? Why don't we use this enormous knowledge? We have to find new ways to do this."

Epilogue

At the end of the event everyone comes together again in plenary. A little tired, but quite content. The participants themselves almost seem to be surprised how far you can get in one day, if you leave your comfort zone and old thinking patterns behind.

Dominik Groß: “In everyday life we take too little time for open-ended creativity.”

Julia Schröder: “It feels good to break out of the silos for a change and put the prefabricated talking points aside.”

Timo Hertwig: “I think the formula is: Big goals, small steps.”

So what remains of the workshop day? A feeling of openness and freedom, perhaps, which hopefully doesn't disappear immediately upon contact with everyday life. The realization that heterogeneous and transdisciplinary groups always produce surprising results. "The idea of getting CO2 certificates for walks and cycling fascinates me deeply," says B. Braun board member Meinrad Lugan. It is interesting, says Julia Schröder, “that both prototypes leave health insurance, as we have known it since Bismarck, far behind. That would be a real change.” Of course, a complex and interdependent system such as the healthcare sector cannot be restarted at the touch of a button. But that’s no reason to stand still. "This agility in thought and action," says Meinrad Lugan, "is particularly important for large corporations like B. Braun.” He can well imagine that within the company health insurance plan, for example, individual health targets can be tried out, as they were proposed by the "System" team. In one of the next board meetings, the topic will be on the agenda anyway. He says, “If there's one thing I've learned today, it's that we don't lack ideas, we lack space.”